By Gideon Osaka

Ngeria’s petroleum industry is once again at a defining crossroads. The resignation of the chief executives of the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) and the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), barely four years after the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) came into force, has triggered intense debate across government, industry and investment circles. Far from being a routine leadership change, the shake-up has exposed deeper tensions within the oil and gas sector over regulation, power, and the future direction of reform.

At the centre of the controversy lies a volatile mix of domestic refining, fuel imports, regulatory credibility and entrenched commercial interests, amplified by a high-profile confrontation involving the Dangote Refinery. As President Bola Ahmed Tinubu nominates new leaders to steer the two powerful regulators, expectations are rising that this moment could either reset confidence in the PIA framework or confirm long-standing fears that structural reform has not gone far enough.

This cover story examines what led to the regulatory exits, what industry experts and stakeholders are saying, and what the new appointments mean for upstream investment, gas development and downstream market stability. More importantly, it asks a critical question: can Nigeria’s petroleum regulation finally shift from institution-building to value delivery in an increasingly unforgiving global energy market?

Nigeria’s petroleum industry rarely changes quietly. When it does, it is almost always because powerful economic interests, politics, and reform ambitions have collided. The resignation of Engineer Farouk Ahmed, Chief Executive of the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA), and Gbenga Komolafe, Chief Executive of the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), represents one such collision, one whose reverberations extend far beyond Abuja.

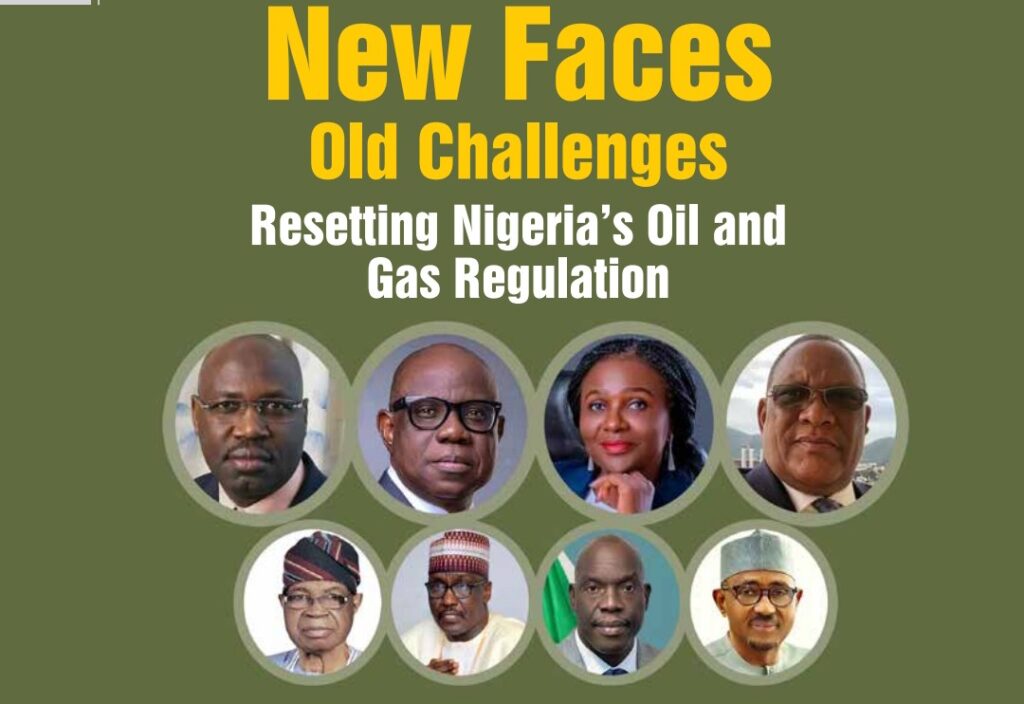

Announced through a State House press release in December 2025, the leadership exits and the nomination of Oritsemeyiwa Amanorisewo Eyesan and Engineer Saidu Aliyu Mohammed as successors have ignited intense debate across Nigeria’s oil and gas ecosystem. At stake is not merely who leads two powerful regulators, but whether the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), hailed as Nigeria’s most consequential energy reform in decades, can finally move from institutional promise to economic performance.

At the heart of the moment lies a deeper struggle: between domestic value creation and entrenched rent-seeking, between regulatory independence and political influence, and between reform rhetoric and lived investor experience.

The End of the PIA’s Foundational Era

Farouk Ahmed and Gbenga Komolafe were not routine appointees. They were foundational leaders, appointed in 2021 by former President Muhammadu Buhari to midwife the PIA into operational reality. Their task was historic and fraught: dismantle old regulatory structures, create new institutions from scratch, and impose order on an industry long characterised by opacity and policy inconsistency.

Under Komolafe, the NUPRC became the custodian of Nigeria’s upstream sector; licensing acreage, enforcing fiscal terms, and seeking to reverse years of declining oil production. Under Ahmed, the NMDPRA oversaw the politically explosive midstream and downstream segments, including fuel supply regulation, product quality certification, imports, and pricing oversight.

Yet four years into the PIA era, the verdict is mixed. While regulatory institutions were established and subsidiary regulations issued, investment inflows failed to meet expectations, crude oil production remained below potential, and gas infrastructure development lagged behind policy ambition. For many stakeholders, the regulators appeared more effective at rule-making than at value-unlocking.

Their resignations, therefore, mark more than personal exits. They signal the close of the PIA’s establishment phase and the opening of a far more unforgiving chapter, one in which results, not structures, will define regulatory legitimacy.

Dangote, Regulation and a Long-Simmering Conflict

The timing of Farouk Ahmed’s exit is particularly significant. It followed moments of escalating public tension between the NMDPRA and Africa’s largest industrialist, Aliko Dangote, whose $20 billion refinery has become both a symbol of Nigeria’s industrial ambition and a lightning rod for regulatory controversy.

Energy analyst Etim Etim, writing via The Cable, contextualised the dispute within Nigeria’s deeply entrenched fuel import ecosystem. According to him, Dangote’s confrontation with the regulator was not new, but it reached unprecedented intensity when the industrialist accused the NMDPRA leadership of monumental corruption.

In Etim’s assessment, Dangote was not merely fighting a regulator but an entire fuel import architecture sustained by powerful commercial interests. He pointed to major fuel importers, including Oando Plc, which, according to the company’s June 2025 press statement, reported ₦4.1 trillion in revenue and ₦220 billion in profit after tax in 2024, despite declining refined product volumes. The implication was clear: fuel imports remain immensely profitable, and domestic refining, no matter how large, threatens established revenue streams. Alongside Oando, companies such as NIPCO, BOVAS, Eternal Oil, A.A. Rano, the NNPC and others continue to dominate the import space.

For Dangote, whose refinery now produces PMS, diesel, aviation fuel and petrochemicals, the conflict symbolises a broader battle between local value creation and import dependence.

Silence, Perception and Regulatory Credibility

Beyond the substance of the allegations, industry analysts were struck by the NMDPRA’s initial silence. Energy analyst Udeme Akpan argued that while conflict is inevitable in petroleum regulation, communication failure is not.

Drawing on the words of late Professor Jibril Aminu, Akpan observed that regulators inevitably step on toes because vested interests in the oil industry are unusually long and deeply rooted. However, he faulted the regulator for allowing damaging narratives to circulate unchallenged for days before issuing a brief disclaimer that failed to address the core issues raised.

In an interconnected global energy market, Akpan warned, regulatory reputational damage does not stop at Nigeria’s borders. Investors, partners and rating agencies watch how disputes are managed as closely as they watch policy texts.

A Long History of Resistance to Domestic Refining

For some industry observers, the Dangote controversy fits into a longer historical pattern. Bello Isiaka Babatunde traced Dangote’s refining journey as a case study in systemic resistance to domestic capacity.

He recalled how:

* Dangote purchased the Port Harcourt Refinery under President Obasanjo, only for the deal to be reversed.

* He subsequently invested over $20 billion in building a greenfield refinery.

* Claims that his products were substandard were later disproved.

* Initial refusal by NNPC to supply crude forced him to import feedstock from the United States.

* Labour disputes, accusations of monopoly, and logistics challenges followed.

Today, Dangote Refinery exports products to the United States, Asia and across Africa, earning foreign exchange at a time Nigeria struggles with FX scarcity. Against this backdrop, Babatunde questioned the rationale of continued large-scale PMS imports.

To many in the industry, this history fuels a belief that regulatory behaviour has at times been misaligned with national economic interest, whether by design or by capture.

A Presidential Reset Under Tinubu

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s response, which accepts the resignations and nominates new chief executives, reflects his broader governing style. From fuel subsidy removal to FX liberalisation, Tinubu has shown a willingness to absorb political shocks in pursuit of structural reform.

Energy sits at the centre of that agenda. Nigeria’s oil and gas sector must simultaneously:

* Generate revenue in a fiscally constrained economy

* Attract investment amid global capital competition

* Anchor a gas-led industrialisation strategy

In this context, regulatory leadership becomes a strategic economic lever rather than a bureaucratic appointment.

Eyesan at NUPRC: Strategic Competence Meets High Expectation

The nomination of Oritsemeyiwa Amanorisewo Eyesan as CEO of the NUPRC has been widely welcomed across upstream circles. With nearly 33 years at NNPC and its successor entities, culminating as Executive Vice President, Upstream, Eyesan brings deep familiarity with joint ventures, production optimisation, and investor engagement.

Energy expert Dr. Francis Adigwe described her appointment as “a square peg in a square hole,” praising her technical competence, integrity and decisiveness. He argued that President Tinubu’s reform momentum, which began with NNPC Limited, is now extending meaningfully into the regulatory space.

Upstream operators told Valuechain that Eyesan understands the economics of barrels, not just the rules governing them. However, goodwill is conditional. She will be judged on approval timelines, fiscal stability signals, and her ability to reverse Nigeria’s production decline.

Saidu Mohammed at NMDPRA: Discipline for a Troubled Downstream

Reaction to Engineer Saidu Aliyu Mohammed’s nomination as CEO of the NMDPRA has been particularly strong among downstream and gas stakeholders. His résumé, spanning Kaduna Refining, Nigerian Gas Company, NLNG subsidiaries, the AKK pipeline and the Gas Masterplan, signals execution capacity rather than regulatory experimentation.

Industry practitioner Gboyega Bello described Mohammed as one of the most principled professionals he has encountered, arguing that his appointment could restore sanity to a downstream sector plagued by inconsistency and unorthodox practices.

For gas developers and infrastructure investors, Mohammed’s experience is reassuring. They see his leadership as an opportunity to de-risk projects, enforce the gas network code, and align midstream regulation with Nigeria’s gas transition ambitions.

A Cautionary Note on Governance and Independence

Not all reactions were celebratory. Petroleum economist Professor Wumi Iledare welcomed the appointments but warned that leadership change alone cannot stabilise the PIA framework.

He argued that the near-simultaneous exit of both regulators less than four years into the PIA era raises questions about institutional resilience. More critically, he warned of the persistence of legacy NNPC culture within agencies explicitly designed to be independent.

For Iledare, the real reform test lies in governance architecture, particularly the constitution of competent, independent boards capable of safeguarding regulatory autonomy. Without this, he warned, reform risks remaining structural in form but shallow in substance.

Scepticism, Power and the Shadow of Allegations

Some stakeholders remain deeply sceptical. Energy commentator Othman Quchi framed the resignations within a broader narrative of power struggles and corruption allegations that continue to haunt Nigeria’s oil industry.

While his language is stark, it reflects a persistent trust deficit. For this constituency, the critical questions are not about résumés but about accountability: whether allegations will be transparently investigated, and whether new leaders will be insulated from political and commercial pressure.

The Industry Watches—and Waits

What unites these diverse perspectives is a shared recognition that Nigeria’s petroleum sector is at a defining crossroads. The PIA has delivered institutions, but not yet transformation. The exits of Ahmed and Komolafe, and the arrival of Eyesan and Mohammed, create a narrow window to reset trust.

The new regulators inherit:

- Heightened public scrutiny

- Investor impatience

- A volatile political economy

They also inherit opportunity: to align regulation with domestic value creation, gas-led growth, and investor confidence.

In the end, Nigeria’s petroleum future will not be determined by policy documents alone, but by whether regulation becomes a catalyst rather than a constraint. For Eyesan and Mohammed, the clock starts on day one. For the industry, patience long stretched will be short.